...what would it be? Could it still be called dialectic? L'economie generale, yes. But this is precisely what is not dialectic in a Hegelian sense (l'economie restreinte).

...what would it be? Could it still be called dialectic? L'economie generale, yes. But this is precisely what is not dialectic in a Hegelian sense (l'economie restreinte).Or is it? After reading him, one is surprised how much Derrida writes on Hegel. On: that is, not necessarily about, nor simply against Hegel. One is suprised how much Derrida writes not against the dialectic simply, but on it, on top of it, like graffiti, writing over it, lifted above it (Aufgehoben, relevé). One is surprised precisely because Derrida does not seem like the generation that wrote most about or against Hegel in France: the generation of Sartre, Lacan, Bataille, Kojeve, Hyppolite, even Althusser--the "existential" generation (in the sense that they react to existentialism in some way, or, better, to Heidegger). In a way he lifts himself above the fray of those thinkers, bogged down in critiquing dialectical reason, in writing against or about it, and thinks the trace and différance. But that he thinks this trace to lift Hegel above being merely written against or about--this is what one does not expect.

Those interested in Derrida need to think hard about this: Derrida does not write about Hegel (or) to critique him. Deconstruction, if it was the name for those writings about the trace and différance, was precisely what allowed him to write on Hegel and not just simply about Hegel or in such a way as to only critique Hegel.

If this was the case, it means that Derrida was not undoing the dialectic, but precisely lifting it above being written against or written about.

One has to think of this "lifting" if one wants to think what this means for the possibility of a Derridian dialectic. As much as it might mean rescuing or saving, "lifting" can also mean to steal, to pilfer. It is a transgression that precisely does not move into the sphere of a beyond, where something can be written about, comprehended, or written against, definitely opposed. The play on raising up out of the fray of "existential" Hegelianism and also stealing this Hegelianism from the "existential" age is precisely what characterizes the Derridian dialectic. It is what is suppressed and elevated by those Derridians who simply think Hegel exists to be critiqued in the texts of Derrida.

In Derrida's time, this play was also what was being suppressed and elevated--precisely not lifted--by Lacanians. And today, their suppression and elevation is the most tempting way to do away with the lifted Hegelianism of Derrida. Zizek, Badiou: they don't lift Hegel, they comprehend him, they are relieved that they are done with Hegel, that he is over with, that he has been finally made to be commensurate with a postmodernism so he can be used ethically against the old Hegelianism, capitalism. Thanks to Derrida--these Lacanians say--we are able to relieved of Hegel without having the guilt of lifting (relevé) him: thanks to Derrida we can now use him against himself when we write about him. But what--they continue--is all this writing on Hegel in Derrida, this talk about lifting, about relève? We can be relieved of Hegel without lifting him! Stupid Derrida! You do not see how against Hegel you can be in writing about him.

What is dangerous and disgusting about this is that it is a refusal to think about how being relieved of Hegel is precisely lifting him--how relieving (relève) is precisely just another translation of lifting (relève).

What is the Derridian dialectic, then? Can we specify this stolen trace, this trace of a trace? Provisionally: the plunge back into the transgression that Hegelian dialectic effectuates in its negations, but tarrying with this transgression as such, with its negativity just at the point (and time) it negates, so as

to make it negate only indeterminately, generally, and yet without reserve. All this means is that the Derridian dialectic is seeing the impossibility of writing against Hegel, and why it could and should always only amount to a lifting of Hegel, a subscription (writing under, which for Derrida is the same as writing on) to the labor of the dialectic. The Derridian dialectic, then, is always a writing on Hegel, a writing that shows how Hegel can never be overcome or elevated (like it is said to be in Zizek, or in Heidegger), never be suppressed.

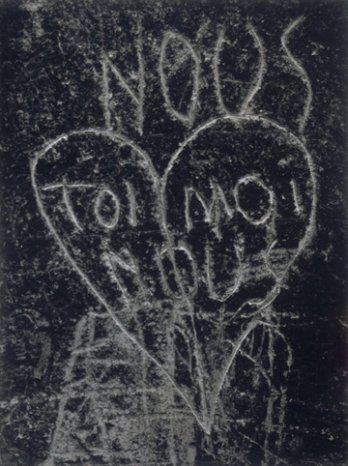

to make it negate only indeterminately, generally, and yet without reserve. All this means is that the Derridian dialectic is seeing the impossibility of writing against Hegel, and why it could and should always only amount to a lifting of Hegel, a subscription (writing under, which for Derrida is the same as writing on) to the labor of the dialectic. The Derridian dialectic, then, is always a writing on Hegel, a writing that shows how Hegel can never be overcome or elevated (like it is said to be in Zizek, or in Heidegger), never be suppressed.But what would this dialectic look like? Again, another provisional specification: it would look like "NOUS" (the French word for "we," and, despite or perhaps because of this, also the Greek word for knowing) written on a wall in the Centre Pompidou, traced by Brassaï. A graffiti that writes on something in order to engage what it can't overcome, what it can't write about or against, a dialectic of what can never be suppressed. That is, an infinite lifting, a stealing of what steals, over and over again without reserve.

I'll write on this more in another post. Sketching the relationship to a Hegelianism that seeks to overcome Hegel, and showing that this is precisely not what Derrida does--that he does not want to be relieved of Hegel without lifting Hegel--is all that is crucial here.