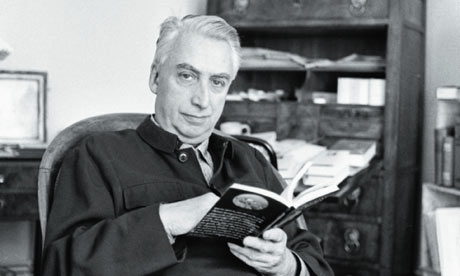

As I'm revisiting Mythologies lately I keep thinking back fondly on Writing Degree Zero, and just how brilliant and important a book that is.

It's also an interesting book from the perspective of our current, post-ironic moment of post-post-modernism or the New Sincerity or whatever you want to call it.

Barthes uses the analogy of the "degree zero"--I do indeed believe he used it as an analogy merely, as he would with various linguistic terms, not stretching them to apply literally scientifically but almost by metaphor extending their range and applicability instead--to talk about the type of writing that he is concerned with. But I do think there was a tendency to interpret this, in the coming years, in certain, other ways.

The degree zero of writing I think for Barthes meant something more like writing that behaved as if it was aware of its status as writing. As such, it was more like writing that was the parody of writing. If it were to manifest itself at its purest, there was something campy about the writing that was writing degree zero. It's like how spaghetti westerns are the purest type of westerns by also being some of the least original, the least authentic. Or the Batman series, which is goofy but more perfect than any other kind of comic book adaptation. All the elements are there, and there is a satisfaction, a YES that you utter privately to yourself when you read some writing of the type Barthes is talking about.

The Pleasure of the Text, despite being a great book, I think may have made this pleasure out to be a more serious thing than it was. Because the pleasure you take in something campy isn't jouissance. Barthes' use of that word was misleading and strange. Only when he later got around to talking about writing and death did he seem to give us an accurate picture of the other face of the satisfaction he was originally talking about: it is something like nostalgia, something like mourning. It isn't what he says it is in this work, which is that sort of bizarre ecstasy that so fascinated Lacan.

But it was an influential interpretation of the kind of reaction to the writing he was originally talked about. And it was of a piece with the times. Self-awareness moving into parody around the time of that text seemed to become a much more serious, but also a much more superficial thing: the enjoyment wasn't in the nearness-to-parody anymore, but in something like the transformation of of the state of discourse, the change in the conversation, that that sort of writing--writing that was understood to be writing--produced.

In short, pleasure in self-awareness seemed to morph into a pleasure in irony, in the way that writing understood as such changed entirely the plane on which we as humans conversed and communicated. No longer was any meaning to be taken literally. Writing as writing was supposed to be the death of literalism.

We all know how well that turned out. Literalism came back with a vengence, and the New Sincerity is in many ways a product of it. But there is, I think, too, an acknowledgment that what most distinguishes irony as a vehicle is that it is safe: for all the crowing about how reckless and dangerous a figure it is, irony is most remarkable for the way that it seals off a domain of discourse from the rest of communicated speech, creates a group of people in the know, and forces others to be included in that group if they want to know the deeper meaning, the other meaning, both simultaneously behind and on the face of the text.

It can't be stressed enough how much this was an attempt, originally, to kill off literalism: in all the bashing of postmodernism that we do now, we forget just how bad literalism is, how bad the master-narratives that evolve out of it genuinely are, and how noble was the effort to try and do away with all that.

But it also can't be stressed enough how interpreting the degree zero of writing not just as a kind of self-awareness, but as a kind of special zone of meaning, makes writing into a very, very safe thing. The pleasure in it that people had, I think, was a kind of pleasure in the sheer fact of its non-literalism. In many ways, it was a reactionary, even a resentful pleasure.

I have recently myself been at war with myself on this issue, as I try and figure out whether my writing is a little too self-aware, and whether it should become more self-aware to the level of being ironic. Revisiting Writing Degree Zero, I found it quite liberating to see just how unironic was the sort of behavior of the text that Barthes was talking about. Irony isn't bad, but self-awareness shouldn't be frowned upon just because it is associated with irony. In many ways, the upshot was for me, was that writing that is self-aware in a way resists being taken ironically, and becomes more purely just a product, just writing. Maybe, then, writing that moves beyond irony isn't a mere reaction against the excesses of postmodernism. Nor does it thereby have to be sincere.

It may simply be really a return to an appreciation of writing as writing, in the sort of innocent pleasure in the corrupted text that knows it is what it is--writing--and that it can't do anything more about that.

Showing posts with label Barthes. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Barthes. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Rallying its qualities

Should I keep a journal with a view to publication? Can I make the journal into a "work"? [...] No, the journal's justification (as a work) can only be literary in the absolute, even if nostalgic, sense of the word. I discern here four motives.

The first is to present a text tinged with an individuality of writing, with a "style" (as we used to say), with an ideolect proper to the author (as we said more recently); let us call this motive: poetic. The second is to scatter like dust, from day to day, the traces of a period, mixing all dimensions and proportions, from important information to details of behavior [...]. Let us call this motive: historical. The third is to constitute the author as an object of desire: if an author interests me, I may want to know the intimacy, the small change of his times, his tastes, his moods, his scruples; I may even go so far as to prefer his person to his work [...] I can attempt to prove that "I am worth more than what I write" (in my books): the writing in my journal then appears as a plus-power (Nietzsche: Plus von Macht), which it is supposed will compensate for the inadequacies of public writing; let us call this motive: utopian, since it is true that we are never done with the image-repetoire. The fourth motive is to constitute the Journal as a workshop of sentences: not of "fine phrases," but of correct ones, exact language: constantly to refine the exactitude of the speech-act (and not of speech), according to an enthusiasm and an application, a fidelity of intention which greatly resembles passion: "yea, my reins shall rejoice, when thy lips speak right things" (Proverbs 23:16). Let us call this motive: amorous (perhaps even idolatrous--I idolize the Sentence).

For all my sorry impressions, then, the desire to keep a journal is conceivable. I can admit that it is possible, in the actual context of the Journal, to shift from what at first seemed to me improper in literature to a form which in fact rallies its qualities: individuation, spoor, seduction, fetishism of language.

-Roland Barthes, "Deliberation," Tel Quel, 1979

The first is to present a text tinged with an individuality of writing, with a "style" (as we used to say), with an ideolect proper to the author (as we said more recently); let us call this motive: poetic. The second is to scatter like dust, from day to day, the traces of a period, mixing all dimensions and proportions, from important information to details of behavior [...]. Let us call this motive: historical. The third is to constitute the author as an object of desire: if an author interests me, I may want to know the intimacy, the small change of his times, his tastes, his moods, his scruples; I may even go so far as to prefer his person to his work [...] I can attempt to prove that "I am worth more than what I write" (in my books): the writing in my journal then appears as a plus-power (Nietzsche: Plus von Macht), which it is supposed will compensate for the inadequacies of public writing; let us call this motive: utopian, since it is true that we are never done with the image-repetoire. The fourth motive is to constitute the Journal as a workshop of sentences: not of "fine phrases," but of correct ones, exact language: constantly to refine the exactitude of the speech-act (and not of speech), according to an enthusiasm and an application, a fidelity of intention which greatly resembles passion: "yea, my reins shall rejoice, when thy lips speak right things" (Proverbs 23:16). Let us call this motive: amorous (perhaps even idolatrous--I idolize the Sentence).

For all my sorry impressions, then, the desire to keep a journal is conceivable. I can admit that it is possible, in the actual context of the Journal, to shift from what at first seemed to me improper in literature to a form which in fact rallies its qualities: individuation, spoor, seduction, fetishism of language.

-Roland Barthes, "Deliberation," Tel Quel, 1979

Thursday, September 2, 2010

Simile

Just ran across one of my favorite similes from Virgil, at the beginning of Book VIII of the Aeneid. But I should say something about similes in general first, because they are very strange things. This is especially true when they take the extended "epic" form, which I actually think is the purest. Now, there are a lot of reasons to think otherwise: the epic simile provides a comparison which does not so much compare as narrate another story in miniature, and when they are not annoying for taking us away from the action, they vex our attempts to make sense of them, as they force even best interpretations to turn towards the awkwardness of allegory.

But many of these reasons come from a sense of the rhetorical canon (it doesn't have to be even an explicit rhetoric) that subordinates the simile to metaphor. Never mind the fact that this tendency often comes from the modern sense of metaphor as a function rather than a--for lack of a better word (the traditional "trope" having been coopted by de Man et. al.) I'll just say an artifice--which tends to justify itself with references the psyche empirically understood. Whether these take place in studies that present the empirical psyche straightforwardly as such (in a marriage of psychology and poetics that begins with I.A. Richards), or studies that veil it in a pseudo-phenomenological garb of anxiety and trauma (in a deconstructivism or late-Lacanianism), such view is problematic--not because empiricism provides its foundation, or because the reference is too psychological, but because such it sees the place where the psyche meets rhetoric as language, which is thereby both kept obscure and granted too much power (it becomes Language). This, by the way, is why this sense of metaphor as a function is really only helpful in structuralist poetics, which interprets the psyche psychoanalytically (as in Barthes) or with a genuine phenomenological intent (Ricoeur often, or the more un-de-Manian aspects of Derrida). Situating the link in a linguistic system which, made up as it is of signs, is able to be studied (that is, neither undifferentiated or wrapped in the mystery of infinite differentiation), these stay true to the real aim of the functional sense of metaphor, best outlined by Jakobson: to recover rhetoric by recovering its explanatory power, which means making it more economical (two tropes, which are brought into closer relationship to schemes) so as to restore some sense of the urgency of debates over typology (it will matter again whether the instance in question is an instance of metaphor or not).

But never mind all that: the point is that everything that makes us subordinate simile to a metaphoric function doesn't help us when it comes time to actually get a sense of the purpose of the simile. Here, it is more helpful to turn things around and say as Pope once did that a metaphor is really just a little simile: this junks all the deeper things we have learned about metaphor, and reduces them to the comparative purpose of the simile, but it gives us a perspective that doesn't take this comparative purpose for granted. More significantly, it changes the relationship between metaphor and simile from one of explicitness (when we think of simile subordinated, we often say that it is just a more explicit metaphor: we are apt to explain it as a metaphor that just "has" like or as) to one of size: we thereby understand the comparison accomplished by the "littler" simile as something more like a short illustration, and the comparison of the actual simile as something elaboration. There is something disgusting to modern ears in this, because it comes close to the late-19th century finishing-school sense of such tropes as ornaments that make everyday speech more noble, decorated, and serve to puff it up. But comparison as elaboration is something different than comparison as ornamentation, and it gives us some sense of the essential role that earlier generations felt such tropes played. For they did not have such a disgusting sense that proper speech should be utterly unornamented, devoid of anything but the most rudimentary grammatical connections and the plainest, most dumbed-down meaning: they did not have the sense that meaning was utterly opposed to the means that expressed it (a sense which is only exacerbated by weak attempts to dissolve this opposition and make everything "linguistic," like those of the empirical/postmodern theories I mentioned above--which is why I complain about them).

If we view the simile then in this light, we understand more its relationship to narrative. Perhaps we even see it see it as a modification of the storytelling impulse itself, a modification which seeks to put the fictional aspect of stories to good use: it seeks to find what in fiction compares or elaborates reality, and uses it to work up a fiction already being elaborated. Such a role might actually bring it more in line with a different, lyric impulse, which does not oppose fiction and reality but sets them side by side: the simile might be lyric trying to tell a story, in other words, or narrative trying to return to its similar lyric-like--sorry for the similes--lack of opposition to reality (considered as something different from history, which is mimetically duplicated--more on this in a moment). This view of similes can perhaps most be opposed to view that has to make sense of them as allegory, relating the components together into a hard lump which, in its self-consistency, opposes itself holistically, at one go, to whatever is being compared: maybe it is even the trope that is the very antidote to allegory itself, being always closer (even in its more condensed, illustrative moments) to something like a parable.

Of course, what challenges such a view is the mimetic function that is most explicit in a simile. But what if we rethought mimesis in our rethinking of this very explicitness above, though we did so in a (supposedly--I'd say seemingly but that's what is precisely in question) different connection? Elaboration, like fiction itself, surely involves mimesis, but is not therefore an elaboration of anything that would bring it into opposition to reality, or, as was often said in the height of a celebration of postmodernity, undermine reality (for similar--sorry again--perspectives on check out the writings of Paul Fry and Michael Wood: Fry has been advancing this "realist" view since the 80's). Once we admit the fact that fiction, with mimesis at its center driving it on, is not as opposed to reality as it is to history (the weird internal timeframe of literature, which you can sit down and slip back into at any time, is an index of this--which does not, for all that, make literature itself something ahistorical), we begin to see how tropes that involve it, that mobilize it, might actually be the stuff of literature that is most in connection with the real.

This probably requires a bit more thought (how does literature's non-opposition to the real differ from its elements? how does a novelistic fiction's elaboration of reality differ from lyric's, which is obviously more direct? and how much is rhetoric fictional, especially when it is used in "non-fictional" [a pejorative term, that brings fiction back into opposition with reality qua history] discourses?). But in the meantime, it certainly shows you why I grant the epic simile primacy, as something like the "model" of all similes, and explains as well perhaps the most fascinating thing about epic similes (and perhaps all similes, then): their amazing translatability. Because from a practical perspective they serve to elaborate first and foremost (or tend to open up into something more than illustration), they gain a certain freedom from the selection of words that tends to modify illustrations (metaphors) more. They differ, of course, from translation to translation, but are wonderfully portable.

Perhaps I'll give you an example with the following simile, to which I finally come:

quae Laomedontius heros

cuncta uidens magno curarum fluctuat aestu,

atque animum nunc huc celerem nunc diuidit illuc

in partisque rapit uarias perque omnia uersat,

sicut aquae tremulum labris ubi lumen aenis

sole repercussum aut radiantis imagine lunae

omnia peruolitat late loca, iamque sub auras

erigitur summique ferit laquearia tecti.

-Book VIII.18-25

Meanwhile the heir

of great Laomedon, who knew full well

the whole wide land astir, was vexed and tossed

in troubled seas of care. This way and that

his swift thoughts flew, and scanned with like dismay

each partial peril or the general storm.

Thus the vexed waters at a fountain's brim,

smitten by sunshine or the silver sphere

of a reflected moon, send forth a beam

of flickering light that leaps from wall to wall,

or, skyward lifted in ethereal flight,

glances along some rich-wrought, vaulted dome.

-Theodore Williams' (pretty literal) translation.

While Turnus and th' allies thus urge the war,

The Trojan, floating in a flood of care,

Beholds the tempest which his foes prepare.

This way and that he turns his anxious mind;

Thinks, and rejects the counsels he design'd;

Explores himself in vain, in ev'ry part,

And gives no rest to his distracted heart.

So, when the sun by day, or moon by night,

Strike on the polish'd brass their trembling light,

The glitt'ring species here and there divide,

And cast their dubious beams from side to side;

Now on the walls, now on the pavement play,

And to the ceiling flash the glaring day.

'T was night; and weary nature lull'd asleep

The birds of air, and fishes of the deep,

And beasts, and mortal men.

-Dryden's translation (I include three more lines because I think Dryden is doing a balancing act of some sort between night and day which nicely takes off from Virgil.)

I'll add other translations as I hunt them down.

But many of these reasons come from a sense of the rhetorical canon (it doesn't have to be even an explicit rhetoric) that subordinates the simile to metaphor. Never mind the fact that this tendency often comes from the modern sense of metaphor as a function rather than a--for lack of a better word (the traditional "trope" having been coopted by de Man et. al.) I'll just say an artifice--which tends to justify itself with references the psyche empirically understood. Whether these take place in studies that present the empirical psyche straightforwardly as such (in a marriage of psychology and poetics that begins with I.A. Richards), or studies that veil it in a pseudo-phenomenological garb of anxiety and trauma (in a deconstructivism or late-Lacanianism), such view is problematic--not because empiricism provides its foundation, or because the reference is too psychological, but because such it sees the place where the psyche meets rhetoric as language, which is thereby both kept obscure and granted too much power (it becomes Language). This, by the way, is why this sense of metaphor as a function is really only helpful in structuralist poetics, which interprets the psyche psychoanalytically (as in Barthes) or with a genuine phenomenological intent (Ricoeur often, or the more un-de-Manian aspects of Derrida). Situating the link in a linguistic system which, made up as it is of signs, is able to be studied (that is, neither undifferentiated or wrapped in the mystery of infinite differentiation), these stay true to the real aim of the functional sense of metaphor, best outlined by Jakobson: to recover rhetoric by recovering its explanatory power, which means making it more economical (two tropes, which are brought into closer relationship to schemes) so as to restore some sense of the urgency of debates over typology (it will matter again whether the instance in question is an instance of metaphor or not).

But never mind all that: the point is that everything that makes us subordinate simile to a metaphoric function doesn't help us when it comes time to actually get a sense of the purpose of the simile. Here, it is more helpful to turn things around and say as Pope once did that a metaphor is really just a little simile: this junks all the deeper things we have learned about metaphor, and reduces them to the comparative purpose of the simile, but it gives us a perspective that doesn't take this comparative purpose for granted. More significantly, it changes the relationship between metaphor and simile from one of explicitness (when we think of simile subordinated, we often say that it is just a more explicit metaphor: we are apt to explain it as a metaphor that just "has" like or as) to one of size: we thereby understand the comparison accomplished by the "littler" simile as something more like a short illustration, and the comparison of the actual simile as something elaboration. There is something disgusting to modern ears in this, because it comes close to the late-19th century finishing-school sense of such tropes as ornaments that make everyday speech more noble, decorated, and serve to puff it up. But comparison as elaboration is something different than comparison as ornamentation, and it gives us some sense of the essential role that earlier generations felt such tropes played. For they did not have such a disgusting sense that proper speech should be utterly unornamented, devoid of anything but the most rudimentary grammatical connections and the plainest, most dumbed-down meaning: they did not have the sense that meaning was utterly opposed to the means that expressed it (a sense which is only exacerbated by weak attempts to dissolve this opposition and make everything "linguistic," like those of the empirical/postmodern theories I mentioned above--which is why I complain about them).

If we view the simile then in this light, we understand more its relationship to narrative. Perhaps we even see it see it as a modification of the storytelling impulse itself, a modification which seeks to put the fictional aspect of stories to good use: it seeks to find what in fiction compares or elaborates reality, and uses it to work up a fiction already being elaborated. Such a role might actually bring it more in line with a different, lyric impulse, which does not oppose fiction and reality but sets them side by side: the simile might be lyric trying to tell a story, in other words, or narrative trying to return to its similar lyric-like--sorry for the similes--lack of opposition to reality (considered as something different from history, which is mimetically duplicated--more on this in a moment). This view of similes can perhaps most be opposed to view that has to make sense of them as allegory, relating the components together into a hard lump which, in its self-consistency, opposes itself holistically, at one go, to whatever is being compared: maybe it is even the trope that is the very antidote to allegory itself, being always closer (even in its more condensed, illustrative moments) to something like a parable.

Of course, what challenges such a view is the mimetic function that is most explicit in a simile. But what if we rethought mimesis in our rethinking of this very explicitness above, though we did so in a (supposedly--I'd say seemingly but that's what is precisely in question) different connection? Elaboration, like fiction itself, surely involves mimesis, but is not therefore an elaboration of anything that would bring it into opposition to reality, or, as was often said in the height of a celebration of postmodernity, undermine reality (for similar--sorry again--perspectives on check out the writings of Paul Fry and Michael Wood: Fry has been advancing this "realist" view since the 80's). Once we admit the fact that fiction, with mimesis at its center driving it on, is not as opposed to reality as it is to history (the weird internal timeframe of literature, which you can sit down and slip back into at any time, is an index of this--which does not, for all that, make literature itself something ahistorical), we begin to see how tropes that involve it, that mobilize it, might actually be the stuff of literature that is most in connection with the real.

This probably requires a bit more thought (how does literature's non-opposition to the real differ from its elements? how does a novelistic fiction's elaboration of reality differ from lyric's, which is obviously more direct? and how much is rhetoric fictional, especially when it is used in "non-fictional" [a pejorative term, that brings fiction back into opposition with reality qua history] discourses?). But in the meantime, it certainly shows you why I grant the epic simile primacy, as something like the "model" of all similes, and explains as well perhaps the most fascinating thing about epic similes (and perhaps all similes, then): their amazing translatability. Because from a practical perspective they serve to elaborate first and foremost (or tend to open up into something more than illustration), they gain a certain freedom from the selection of words that tends to modify illustrations (metaphors) more. They differ, of course, from translation to translation, but are wonderfully portable.

Perhaps I'll give you an example with the following simile, to which I finally come:

quae Laomedontius heros

cuncta uidens magno curarum fluctuat aestu,

atque animum nunc huc celerem nunc diuidit illuc

in partisque rapit uarias perque omnia uersat,

sicut aquae tremulum labris ubi lumen aenis

sole repercussum aut radiantis imagine lunae

omnia peruolitat late loca, iamque sub auras

erigitur summique ferit laquearia tecti.

-Book VIII.18-25

Meanwhile the heir

of great Laomedon, who knew full well

the whole wide land astir, was vexed and tossed

in troubled seas of care. This way and that

his swift thoughts flew, and scanned with like dismay

each partial peril or the general storm.

Thus the vexed waters at a fountain's brim,

smitten by sunshine or the silver sphere

of a reflected moon, send forth a beam

of flickering light that leaps from wall to wall,

or, skyward lifted in ethereal flight,

glances along some rich-wrought, vaulted dome.

-Theodore Williams' (pretty literal) translation.

While Turnus and th' allies thus urge the war,

The Trojan, floating in a flood of care,

Beholds the tempest which his foes prepare.

This way and that he turns his anxious mind;

Thinks, and rejects the counsels he design'd;

Explores himself in vain, in ev'ry part,

And gives no rest to his distracted heart.

So, when the sun by day, or moon by night,

Strike on the polish'd brass their trembling light,

The glitt'ring species here and there divide,

And cast their dubious beams from side to side;

Now on the walls, now on the pavement play,

And to the ceiling flash the glaring day.

'T was night; and weary nature lull'd asleep

The birds of air, and fishes of the deep,

And beasts, and mortal men.

-Dryden's translation (I include three more lines because I think Dryden is doing a balancing act of some sort between night and day which nicely takes off from Virgil.)

I'll add other translations as I hunt them down.

Monday, August 3, 2009

Demystifying literature: de Man and the singular

You all know I'm skeptical of de Man: I think that through equivocation on crucial issues he mislead theorists so much they are only now beginning to realize the extent of the damage. But this doesn't mean he wasn't also brilliant, or that his works aren't extremely useful. In other words de Man's power to mislead only came with a certain type of earned authority. It's just that his words require you to never let your guard down.

You all know I'm skeptical of de Man: I think that through equivocation on crucial issues he mislead theorists so much they are only now beginning to realize the extent of the damage. But this doesn't mean he wasn't also brilliant, or that his works aren't extremely useful. In other words de Man's power to mislead only came with a certain type of earned authority. It's just that his words require you to never let your guard down.This is even more important to remember when these words are strung together in the witty remark, the teachable fragment, the slogan, the aphorism--I'm not sure what exactly to call these particular segments in de Man's corpus. These remarks--like "the resistance to theory is itself theoretical," or "scholarship has, in principle, to be eminently teachable," or "it is better to fail in teaching what should not be taught than to succeed in teaching what is not true" (all three taken only from "The Resistance to Theory")--remain influential even today: though it is important to keep in mind the limits of de Man's influence (as is only appropriate when such an uncritical notion as influence is used), which to this day has not been sufficiently mapped out, such phrases still guide our attempts to articulate what, at bottom, we're doing.

Such a delicate, yet dangerous string of words I want to look at right now:

When modern critics think they are demystifying literature, they are in fact being demystified by it.

-"Criticism and Crisis" (1967, updated in 1970), in Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism, 3-19, 18

As you can see, this is not only highly polemical, but is also conveniently short, pithy, repeatable. One can imagine many theorists picking it up and using it in all sorts of situations. But it would be a mistake to see it merely as a general statement just about anyone. Like most de Manian formulations, it is very precise. The task, then, is not to pull apart what is actually being said here from the sweeping, polemical force of the statement. Instead, it is to see that specificity alone gives such theoretical statements power. The trick of de Man's aphoristic formulation (and it is indeed a dirty one) is to let you think that theory must become less polemical as it gets more specific. Or (and this is oddly more likely), if it does allow you think otherwise, if it allows you to see polemic and precision's incompatability as superficial, it becomes your responsibility to assert this (which makes the trick even dirtier). But we'll try and get specific while also not taking over all the responsibility: we will remain critical of de Man insofar as he engages in a ruse that turns us all into his interpreters--or, better, his "demystifiers."

But, as we were saying, it isn't enough to see de Man's statement as just applying to anyone: we have to ask, first, who these "modern critics" that "demystify" actually are. Ironically, after all we just said, de Man isn't as specific as he should be about this: his answer is, the New Criticism and structuralism, or, rather, the New Critical tendency in American criticism (we can call it by its much misunderstood name: "practical criticism") as it is affected by structuralism coming from France. That's a lot of criticism, enough to seem like the most significant criticism in America and abroad (in other words, another trick involving sweeping generalizations). But it isn't enough to exhaust the totality of the field--not nearly enough, if we have the right view of things.

Why, then, this general practical criticism/structuralist poetics nexus, and not something else? Here de Man is most precise. Both, he says,

consist of showing that certain claims to authenticity attributed to literature are in fact expressions of a desire that, like all desires, falls prey to the duplicities of expression.

-"Criticism and Crisis," 12

This is what he calls "demystifying" literature. Let's be clear about what this process of demystification entails, according to de Man, for the above definition remains only a sliver of what he has to say about it. De Man goes on to say that the authenticity attributed to literature is in fact reducible to the notion--popular before the New Critics and before the advent of structural linguistics--that literary language was of a different nature than the system of language we normally use. (This, by the way, leads to the notion that the experience of this language is of a different order than everyday experience, or what I.A. Richards called, quite accurately, "the phantom aesthetic state:" the two notions imply each other and Richards, in the opening of his Principles of Literary Criticism, moved from this phantom state to this phantom literary language.) The process of demystification then would involve showing that a normal language system could serve as an adaquate basis for interpreting literature. One can see the task that the structuralist poeticians and practical critics, then, oddly have in common--and why de Man rightly groups them together: in the case of practical criticism, the task is to show that normal usage, or in fact everyday usage, provides us with enough meanings that we can outline possible interpretations of what the poem or prose work may be saying; in the case of structuralist poetics (which has a bit more complications I might get into below), the task is to outline how the system of signifiers that linguistics has studied can account for the work in question. Everyday language and the linguists' language both rid us of the need for any priveliged sort of literary language, which would be different in essence.

The larger meaning of de Man's statement becomes more and more obvious: both of these modes, in trying to undo the privilege accorded to literature, fall prey to its privilege. The implications are clear too: de Man is arguing for the restoration of a notion that literary language is different than the system of language we use everyday.

But before we outline what this really means, I would like to return to de Man's quote above regarding demystification. For while demystification involves a certain notion of literary language, it also proceeds in a certain manner which the quote makes clear: armed with her notion that the privelige accorded to literature can be accounted for by everyday language or the structure of language, the demystifying critic shows that the privelige is merely the expression of a desire. This shall remain even more important for us, for it means that demystification involves, prior to the critic's having any very clear notion about the proper sphere of literary language, a certain operation, a method, a "strategy" as de Man indeed calls it (13). Demystification is first and foremost the process of asserting that what is there can be the expression of something the critic, but not you, can see: a desire that is not fully apparent, that is duplicitous, and that needs the critic in order to make its full manifestation. Literature for the demystifier would then lack its "priveliged" or "authentic" status for another reason: literature could not be something impenetrable to the critic's process of making the work fully manifest, and in this respect could not be of a different nature than the critic's language. This, I claim, is the deeper reason behind de Man's notion that demystification involves dissolving literary language into everyday language: it is what in other essays he calls the critic's belief in the phenomenality of literature, the notion that it is something that can be made manifest and, moreover, can, eventually, be made fully manifest. One can also see that it involves a certain notion of the literary object requiring a consciousness that can judge it: in this respect the belief in the phenomenality of the literary work is also a belief in its fundamentally aesthetic nature--the work is there to produce judgments (Kant, of course, gave this view its most concentrated expression). We can also emphasize that it is aestheticism in a different, more perjorative sense: the critic, in this view, is the only one who can complete the artwork by mastering its duplicities, which makes her of the same nature as the artist, and their criticism, in turn, something participating in the art.

But, back to the point: if demystification involves asserting that there is more to the work, in the sense that there is something about it which is not as it seems and can eventually be made clear, when modern critics think they are demystifying literature, they are demystified by it means that they are only making more explicit their inability to see that literature may perhaps not be something that manifests itself.

Now, there are two ways to justify this particular assertion. De Man's way, in the essay in question, is by stressing the fictionality of literature. What he says prior to his little aphorism makes this clear enough:

It [fiction] is demystified from the start.

-"Criticism and Crisis," 18

That is, demystifying a literary text makes nothing in it manifest. This is not because criticism is powerless when confronted by it, but rather because the text's nature qua fictional is to disturb manifestation itself. This is a point not stressed enough--we overlook it constantly in talking about characters, say--but it perhaps lays too much stress on fictionality: de Man could be challenged by bringing up testimony, for example (Derrida, for one, does not evade this: his reading of Blanchot's "The Instant of My Death" in the slim but profound Demeure precisely investigates the possible weave between these two).

I will take the other route and justify the notion that literature does not manifest itself by talking more about what the demystifier supposes literature actually does. The easiest case would be a practical critic, who tries ultimately to establish a meaning for the text. Jonathan Culler shows why this is questionable. Instead, a better case for now would be the structuralist poetician. I'll take Roland Barthes, with his powerful notion of codes in S/Z.

The five codes Barthes considers are extremely useful. They aren't ultimately very rigorous tools to use, but they are so handy and so intuitive: Barthes constructs them in such a way that to an experienced critic they fit like a glove--only allowing actual reflection on the manipulation ultimately produced. In short, in the codes Barthes makes explicit something the critic has for a long, long time engaged in, but never reflected on at such length (this is why they are not to be unreflectively used like any old tools, as Kaja Silverman does in The Subject of Semiotics). This is pointing out the saturation of the text with a certain type of non-literal language which is, unless we want to stretch the word, nevertheless not figurative. He opens up a domain in which a certain understanding of the message is brought about which nevertheless does not have to deal with meaning (that is, literal or figurative, strictly speaking). The code remains the way that parts of the text (and remember this remains pertinent only for a classic text, which is not stressed enough) try to be received in a certain way: as such it is like innuendo, except with the final meaning subtracted, as it were, or made unncessary to grasp.

The cultural codes are, in particular, the most intuitive to the critic (they are also the most boring of the codes: the proairetic and hermeneutic are much more interesting and indeed useful). One understands, in other words, a character has a certain status by the mention of what he wears. Or one understands a fragment of a sentence about abstruse academics, say, not because of the meaning but because of the cultural doxa, which states that academics have no connection to the real world.

The critic then goes through the text and points out these codes: it is what we do especially when watching TV, say, and noting how a certain type of character is stereotypically treated. What is one doing in such an instance? What de Man would say is, precisely, that one is trying to manifest something in the work. Even though the code isn't dealing with meaning, it is nevertheless there to bring something to the fore. It is, in fact doing something even more than that: it is allowing a secure transit between the work, on the one hand, and culture on the other. By pointing out doxa in literature or other, similar artforms, what we are doing is supposing an almost immediate link between the forces which construct the code and the code itself as we find it in a particular message. In pointing it out, we believe we are directly in connection with those societal forces, on some level, and transform them in the act. Why? Because we suppose that the message is not already demystified--to use the quote above--or in other words we overlook the fact that there there may be nothing to manifest in the message except the cultural forces which produce it.

To be clearer, manifestation may not be necessary because the literary work is singular. That means it does not express or represent those cultural and societal forces, but merely is a product of them--indeed, uniquely, irreducibly so (the reduction, in other words, would be to representation). Or, to put it another way, manifestation may not be necessary because the link between a the coded literature and culture is never immediate: it is always and only a set of productive relays which may indeed make manifestation possible, but never necessary for the work to be both extant and also (this is the tough part) able to be criticized.

With this made clear, we now understand how de Man proposes to restore the difference between literary language and ordinary language: it is not by giving literary language an essence, but rather by subtracting it. Literary language is singular, irreducible. And this does not mean the literary work is thereby shut off in any way from ordinary language, culture, or society, but is indeed precisely produced by them--since the connection is not presumed to be simply, unproblematically, indeed naively immediate. It is, in other words, produced in a way that cannot be reduced to the production of something destined to be manifest, and therefore demystified. I'll stop here, but it now should be somewhat clearer why modern critics are being demystified by such a singular literature in demystifying it.

Saturday, July 25, 2009

As a mechanism

Sarrasine interrupts La Zambinella’s confession that she is a castrato:

Sarrasine interrupts La Zambinella’s confession that she is a castrato:“I can give you no hope,” she said. “Cease to speak thus to me, for they would make fool of you. It is impossible for me to shut the door of the theatre to you; but if you love me, or if you are wise, you will come there no more. Listen, monsieur…” she said in a low voice.

“Oh, be still!” said the impassioned artist. “Obstacles make my love more ardent.”

-Balzac, Sarrasine

Barthes comments:

If we have a realistic view of character, if we believe that Sarrasine has a life off the page, we will look for motives for this interruption (enthusiasm, unconscious denial of the truth, etc.). If we have a realistic view of discourse, if we consider the story being told as a mechanism which must function until the end [my italics], we will say that since the law of narrative decrees that it continue, it was necessary that the word castrato not be spoken.

-S/Z, LXXVI

We have all felt this at some point. Characters act improbably because of narrative requirements. But rather than cynically turn our gaze to the writer, and just say that this problem stems from the requirements of composition, the structuralist allows the literary system to absorb the problem, folding the contradiction back into its text—the “common sentence.” Thus Barthes goes on to say say that these two views “support each other:”

A common sentence is produced which unexpectedly contains elements of various languages [my italics]: Sarrasine is impassioned because the discourse must not end; the discourse can continue because Sarrasine, impassioned, talks without listening… From a critical point of view, therefore, it is as wrong to suppress the as it is to take him off the page in order to turn him into a psychological character (endowed with possible motives): the character and the discourse are each other’s accomplices.

-S/Z, LXXVI

But is particularly structuralist is that this text is still an effect of discourse (this, by the way, is what distinguishes Derrida's text from Barthes). In other words, critical analysis is always on the side of discourse:

Such is discourse: if it creates characters, it is not to make them play among themselves before us but to play with them, to obtain from them a complicity which assures the uninterrupted exchange of the codes: the characters are types of discourse and, conversely, the discourse is a character like the others.

-S/Z, LXXVI

Discourse wins, despite the reciprocity. Otherwise characters would play among themselves, in an imaginary literary world. The mechanism keeps working, and as it absorbs contradictions it also absorbs the “realistic view of character.” And rightly so, though this announces a limit to structuralism of sorts: we can’t look at character as some sort of motivated, coherent subject. Why? Because this completely fails to grasp the literary system as literary—that is, fictional. Furthermore, it does not allow us to distinguish basic functions: for example, there is a distinct difference between the improbable act of a character due to the needs of the story, and an improbable act of a character that actively delays the unfolding of a story. The first is what is under discussion here, as we consider the literary system “which must function until the end.” The second forms a subset of the first: it is precisely an effect of this functioning, which Barthes rightly calls a unit of the hermeneutic code. (It is notable that “end” in Barthes statement then does not mean merely a temporal end: it is—in accordance with structuralist notions of finitude—a spatial limit. Schlovsky, for example, cannot distinguish between the two.)

Thus, character is a tying together of various strands of the text, even if viewing them as personalities is somewhat legitimate. Because the looking at the text qua text can absorb this psychologistic view, however, as far as structuralism is concerned, there is no question who is ultimately the authority: the psychologistic view has no comparable ability to explain the textual phenomena except by evading the matter and cynically going to the author or denying fictionality. Barthes can sum up the structuralist view of character quite simply as follows:

When identical semes traverse the same proper name several times and appear to settle upon it, a character is created. Thus, the character is a product of combination: the combination is relatively stable (denoted by the recurrence of the semes) and more or less complex (involving more or less congruent, more or less contradictory figures); this complexity determines the character’s “personality,” which is just as much a combination as the odor of a dish or the bouquet of a wine. The proper name... referring in fact to a body… draws the semic configuration into an evolving (biographical) tense.

-S/Z, XXVIII

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

The Barthesian activity, part 2

Who other than Barthes would have said the following about the novelistic?

Who other than Barthes would have said the following about the novelistic?…the novelistic is neither the false nor the sentimental; it is merely the circulatory space of subtle, flexible desires; within the very artifice of a “sociality” whose opacity is miraculously reduced, it is the web of amorous relations (“To the Seminar,” an excellent text).

That is, who would have said “‘sociality’ whose opacity is miraculously reduced?” This is a way of conveying that what Lukács calls the “world of convention” (Theory of the Novel) in the novel is porous, indeed “circulatory,” “flexible.” But this is inverted unexpectedly and shown in terms of its thickness, its opacity, which is accordingly “reduced.” Barthes can not only effortlessly accomplish such an inversion: he can make it stick (like the referent, like the “real”) by getting it right, by saying the consistent thing, what accords, what would seemingly succeed or follow. This is what I was getting at in talking about activity and its tendency to frustrate the paradigmatic (to “outplay” it, as Barthes says in The Neutral), by tending to be more dynamic, more syntagmatic: activity is la succession réglée d'un certain nombre d'opérations. To put it bluntly, Barthes’s use of metaphor here (and nearly everywhere else) tends to be more metonymic than we might expect (though it is not reducible to this second, opposing, paradigmatic or metaphorical term). One can wonder, however (and Barthes himself wondered this), just how long this succession can go on.

Monday, June 15, 2009

The Barthesian activity

How many people would have written “the structuralist activity,” as Roland Barthes did? That structuralism is an activity, as “la succession réglée d'un certain nombre d'opérations,” rather than a methodology, a school, or a vocabulary (the alternatives that famous essay entertains), or something else altogether, is by no means obvious. But it is typical of Barthes, who sees things in the light of their capability to become, like écrire itself (“To Write, an Intransitive Verb?”), less merely active, or simply opposed to passivity, even as they become more intransitive, richer, more forceful. It also frustrates those who would like to see activity described in the more definite (more active, yet less neutral) terms of practice.

How many people would have written “the structuralist activity,” as Roland Barthes did? That structuralism is an activity, as “la succession réglée d'un certain nombre d'opérations,” rather than a methodology, a school, or a vocabulary (the alternatives that famous essay entertains), or something else altogether, is by no means obvious. But it is typical of Barthes, who sees things in the light of their capability to become, like écrire itself (“To Write, an Intransitive Verb?”), less merely active, or simply opposed to passivity, even as they become more intransitive, richer, more forceful. It also frustrates those who would like to see activity described in the more definite (more active, yet less neutral) terms of practice.For prior to having any particular object in mind, before narrative, before photographs, before myths, Barthes concerns himself with activities, and insofar as he does so what matters less is who performs them or what their effects are. The important thing is not to get the real object, but to get at its activity—which means adding intellect to the object, if I can use an intelligent phrase with which Barthes describes structuralism itself (and I think I can, not because Barthes himself is a structuralist, but because he himself shares in the structuralist activity: of fabricating a functionally analogous world, reflecting and creating all at once—which is by no means a great description of structuralism).

The consequence of this, which should be noted by those privileging practice, is that practice thereby becomes rare (“the rarest text,” in “To the Seminar”), recovers its difference. At the same time, an activity without a real object, without actors or effects, with rare (here, not rarefied, but also seldom) forays into practice, has to be questionable for us: it is, at the very least, vague, and no doubt leads another camp to savor the Barthesian activity precisely in that aspect which allows it to pose as, to play as practice.

But we find already that this skepticism, as well as this enthusiasm, is a bit misplaced: both miss what is crucial, namely what we can call, with Peter Brooks, the “fluid and dynamic” aspect of the activity. It comes from the neutrality we talked about earlier, and how this neutrality, this undoing of activity needs to be described as a “regulated succession:” it is that activity, considered as a succession, as sequence, as closer to syntagm than paradigm (even though it attempts to remain irreducible to either), which makes up the Barthesian activity.

I'll elaborate upon this in another, more thorough post on S/Z.

Saturday, May 30, 2009

Barthes, the syntagmatic

The syntagm presents itself in the form of a 'chain' (the flow of speech, for example). Now as we have seen [earlier in the Elements], meaning can arise only from an articulation, that is, from a simultaneous division fo the signifying layer,and the signified mass: language is, as it were, that which divides reality [...]. Any syntagm therefore gives rise to an analytic problem: for it is at the same time continuous and yet cannot be the vehicle of a meaning unless it is articulated. How can we divide the syntagm? This problem arises again with every system of signs: in the articulated language, there have been innumerable discussions on the nature [...] of the word, and for certain semiological systems, we can here foresee important difficulties. [That is, the problem is not just in linguistics--it also has pertinence for semiology.] True, there are rudimentary systems of strongly discontinuous signs, such as those of the Highway Code, which, for reasons of saftey, must be radically different from each other in order to be immediately perceived; but the iconic syntagms, which are founded on a more or less analogical representation of a real scene, are infinitely more difficult to divide, and this is probably the reason for which these systems are almost always duplicated by articulated speech (such as the caption of a photograph) which endows them with the discontinuous aspect which they do not have.

The syntagm presents itself in the form of a 'chain' (the flow of speech, for example). Now as we have seen [earlier in the Elements], meaning can arise only from an articulation, that is, from a simultaneous division fo the signifying layer,and the signified mass: language is, as it were, that which divides reality [...]. Any syntagm therefore gives rise to an analytic problem: for it is at the same time continuous and yet cannot be the vehicle of a meaning unless it is articulated. How can we divide the syntagm? This problem arises again with every system of signs: in the articulated language, there have been innumerable discussions on the nature [...] of the word, and for certain semiological systems, we can here foresee important difficulties. [That is, the problem is not just in linguistics--it also has pertinence for semiology.] True, there are rudimentary systems of strongly discontinuous signs, such as those of the Highway Code, which, for reasons of saftey, must be radically different from each other in order to be immediately perceived; but the iconic syntagms, which are founded on a more or less analogical representation of a real scene, are infinitely more difficult to divide, and this is probably the reason for which these systems are almost always duplicated by articulated speech (such as the caption of a photograph) which endows them with the discontinuous aspect which they do not have.-Elements of Semiology, III.2.2

For some reason this is a clearer explanation to me of why photographs need captions than all the others I hear (regarding that famous thesis people attribute to Barthes, citing his essays on photography). Barthes then says the following about the syntagm--a very concise and provocative formulation:

In spite of these difficulties, the division of the syntagm is a fundamental operation, since it must yield the paradigmatic units of the system: it is in fact the very definition of the syntagm, to be made of a substance which must be carved up.

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Prior to a hermeneutics and a history

Literature, instead of being taught only as a historical and humanistic subject, should be taught as a rhetoric and a poetics prior to being taught as a hermeneutics and a history.

Literature, instead of being taught only as a historical and humanistic subject, should be taught as a rhetoric and a poetics prior to being taught as a hermeneutics and a history.-Paul de Man, "The Return to Philology"

The power of this formulation comes right from the "prior to," and the fact that both "hermeneutics and history" are thereby conceived as something that "rhetoric and poetics" can actually (perhaps) do without. De Man makes us think not only of undoing the humanist function of the aesthetic object, which makes us "move so easily from literature to its apparent," but superficial, de Man would say, "prolongations in the spheres of self-knowledge, religion, and of politics"--in short that makes us fall prey to ideology in de Man's sense of the term (that which lets us think reference can be grasped precisely by referential means, in short that can allow us to turn literature into a grammar which can then be hermeneutically or historically decoded). He begins to show us that rhetoric, say, is not beholden to its hermeneutical basis except as a possible auxiliary function of its own (perhaps sovereign) operation. In other words, he begins to show us that rhetorical and poetic analysis can be "an examination of the structure of language prior to the meaning [the analysis] produce[s]" (i.e. it can be what he calls a philology, which is what he is defining in this quote right here: and thus we can now understand his extremely equivocal phrasing--the return to rhetoric [to study that proceeds by anti-hermeneutic means] is a return to philology [to the generation of results, of ends that are anti-hermeneutic]). This is not only powerful but radical--and should serve as some check on my dismissals of de Man in my last post. But this way of putting it also comes with increasing dangers--with a vagueness in its radicality.

How? Let's return to the ideological function that I just outlined. For de Man, we move much too quickly between literature to "apparent prolongations in the spheres of self-knowledge, of religion, and of politics" because we precisely make literature into what, through a decoding, just is a set of statements about these three (or more) spheres. This, in his eyes, is precisely the aesthetic ideology: the function of the aesthetic object is to deproblematize precisely this move from what the object is doing to its effects in these spheres (which are the spheres of humanism). Conceiving the work as aesthetic means only to conceive it itself as a prolongation of these spheres (and thus as humanist). You can see even more visibly de Man's desire to expose this as ideology, and oppose it systematically with rhetorical analysis, in his outlining of a literature course (Literature Z) in a fascinating memo from 1975: courses as they have traditionally been taught see

...literature as a succession of periods and movements that can be articulated as an historical narrative. With regard to individual works, the conception is essentiall paraphrastic and thematic, the assumption being that literature can be reduced to a set of statements which, taken together, lead to a better understanding of human existence. Literary studies then become, on the one hand, a branch of the history of culture and, on the other hand, a branch of existential and anthropological philosophy in its individual as well as its more collective aspects.

-"Proposal for Literature Z"

For de Man this is extremely debatable, however nice it is. For what is clear is that all this relies upon a process of exposing the prolongations that are supposedly already there: i.e. a hermeneutics and historical analysis. We find the meaning that is already there. De Man simply asks us to think about whether we can be sure meaning is there or not--and this is enough to begin to dispel the ideology: "the anthropological function of literature cannot be examined with any rigor before its epistemological or verbal status has been understood," he continues, which means that we have to think about what the thing is that we so quickly conceive of as a prolongation of our self-knowledge. Is it really such a thing that we can interpret unproblematically? That we can decode? Hermeneutics and history work in tandem with and ideology of aesthetics to shut down this avenue of inquiry. In this respect what they do is--as he says--actually veil the literariness of literature and prevent its reading.

These last phrases--which are more than polemical (I'd say they are equivocal, nominalist, and dangerous)--are taken from his other most concentrated engagement with these questions, "The Resistance to Theory." This is where the more precise language about reference that I use above is brought in (it is also present in Allegories of Reading): in short it is not only literariness that gets seen as a prolongation of effects of humanist self-knowledge, etc. but the workings of language itself (thus the grammar, the meaning that it is turned into is a humanist grammar, a grammar of these spheres). But let's stay with the danger (and witness de Man outlining these more precise effects of grammar etc.) in that essay:

To stress the by no means self-evident necessity of reading implies at least two things. First of all, it implies that literature is not a transparent message in which it can be taken for granted that the distinction between the message and the means of communication is clearly established. Second, and more problematically, it implies that the grammatical decoding of a text leaves a residue of indetermination that has to be, but cannot be, resolved by grammatical means, however extensively conceived. The extension of grammar to include para-figural dimensions is in fact the most remarkable and debatable strategy of contemporary semiology, especially in the study of syntagmatic and narrative structures. The codification of contextual elements well beyond the syntactical limits of the sentence [see Barthes S/Z and my last post] leads to the systematic study of metaphrastic dimensions and has considerably refined and expanded the knowledge of textual codes. It is equally clear, however, that this extension is always strategically directed towards the replacement of rhetorical figures by grammatical codes. The tendency to replace a rhetorical by grammatical terminology [...] is part of an explicit program, a program that is entirely admirable in its intent since it tends towards the mastering and clarification of meaning. The replacement of a hermeneutic by a semiotic model, of interpretation by decoding, would represent, in view of the baffling historical instability of textual meanings (including, of course, those of canonical texts) a considerable progress. Much of the hesitation associated with "reading" could thus be dispelled.

The argument can be made, however, that no grammatical decoding, however refined, could claim to reach the determining figural dimensions of a text...

-"The Resistance to Theory"

You see, this last move is what is crucial: de Man then expands what remains his question--whether literature is something that can be decoded--into a conclusion. Literature is, indeed, something that cannot be decoded. Look again at all the limits being set up: "no grammatical decoding, however refined, could claim to reach..."; "a text leaves a residue of indetermination that has to be, but cannot be, resolved by grammatical means, however extensively conceived." How can he be sure of this? In the same process what he does is actually define terms like "reading" to apply only to modes of analysis that conclude, like he does, that there just are spheres that can't be reached by grammar. This is how, in the above, he is able to dismiss semiology, which, as Barthes was so good at doing, precisely is trying to responsibly (clearly) get at the aspects of meaning that lie beyond what can be easily decoded. In S/Z codes don't, as de Man here puts it, strictly decode: they arrange themselves into a structure which we are, at the end of the day, quite unsure what to do with. And this to me seems quite resistant to a hermeneutic model, and can't just be dismissed as grammar by another means--as de Man does above.

In short the risk, the danger, is in this: de Man conceives rhetoric, and the reading of rhetoric as only operating in those spheres that a hermeneutics or a history, which see the text as a grammar, cannot penetrate. But this definition is only a negative one. As soon as this "cannot" becomes positive, what he is doing is actually acting as if he is sure about the content of this rhetorical sphere, of this indeterminacy--and it is on this basis that he can dismiss something like semiology. For if "a text leaves a residue of indetermination" how can de Man be so sure that this indetermination "has to be, but cannot be, resolved by grammatical means, however extensively conceived?" Frankly, there is no way to make this sentence make sense. We just cannot be sure that the indetermination will not be resolved precisely by grammatical means if the indetrmination is indeed indeterminate (this is where Derrida and de Man part ways, in my book).

But the point then is that de Man outlines a principle of resistance to hermeneutics that has, really, no basis. He outlines how the aesthetic ideology is complicit with hermenetutics, but then gives you an alternative that only consists in asserting that hermeneutics "misses the literariness of the literary"--which I think means nothing. It means nothing not because this literariness is beyond or anti-hermeneutics--i.e. because the project of finding a mode of analysis that is not hermeneutic is bunk (I think it remains, still, perhaps the greatest task we have to undertake). It means nothing because de Man is still too sure of what the this literariness looks like: in short, because it is merely defined negatively as the anti-hermeneutic, as rhetoric.

So what we get is a powerful formulation, which envisions a space for us beyond a hermeneutics and a history. But it gives us nothing to work off of except our own hatred for hermeneutics and history. This is what is dangerous about de Man. It seems, in my view, much better to go the route of semiology that he precisely outlines here--the grammatization of the rhetorical. For I do think that while de Man is very sensitive to the problems of making the rhetorical grammatical, he himself also ends up doing the same thing in being so confident about what the rhetorical consists of (it is precisely what cannot, cannot, no no no, ever, be reduced to grammar--and this extends into his allegorical readings, though to prove that takes another post). And at the same time, this hatred manifests itself through the equivocation of terms like "reading" and "literariness," which suddenly are terms that function only negatively and in order to castigate other critics: you must not miss the literariness, you are missing it, you are not reading, no no no--I on the other hand do understand it, I read, etc. In short, he gives us something extremely valuable, but he also--by the way he puts it--trains a lot of critics to be only good at shutting down other readings without any reasons for doing so. And this is extremely dangerous.

But I don't want to end just by condemning de Man. I just think his target is wrong: the grammatization of rhetoric is not the threat. The threat is in not seeing the necessity of rhetorical reading in the first place as an alternative to hermeneutics--in being subject to the aesthetic ideology, in his words. Insofar as he makes this clear to us--and he does I think in saying that literature should be taught "as a rhetoric and a poetics prior to being taught as a hermeneutics and a history"--what he is doing is crucial.

(A postscript: what I find dangerous is quite clear--he provides a critical vocabulary that allows others to take it up for, basically, evil ends--and I'm not the first to say this about de Man. But perhaps this position can be countered. Perhaps what de Man is doing in "training a lot of critics to be only good at shutting down other readings" is precisely a less responsible, but somewhat excusable version of something I have argued elsewhere. Actually echoing de Man [in "The Return to Philology" but also elsewhere], I say that theory displaces the evaluative function one found in literary criticism or in the humanities education prior to [and as a concern throughout] the New Criticism and the institution [beginning] of our profession. If we take this notion up, we might see de Man teaching us how to shut down readings in order to teach us to be theoretical in one specific sense--to articulate evaluations in terms that are theoretical and concerned more with the possibilities of their own utterance. I still say this is a very, very dubious way of going about this--at what point do we stop and just say that behind the theory is really just a power-grab? But at another level we can't just say de Man was completely ignorant of the fact that each one of his terms actually was formed to produce the capability of this bad use. I think, in the end, that both things are true: he was quite aware he was disseminating things that could be used maliciously, perhaps more easily than they could be used correctly, but that he also believed perversely that this would change the face of literature, in the long run, for the better--that is, even if it came at any cost...)

Friday, April 24, 2009

Rhetoric as a second linguistics

From the point of view of linguistics, there is nothing in discourse that is not to be found in the sentence: "The sentence," writes Martinet, "is the smallest segment that is perfectly and wholly representative of discourse." Hence there can be no question of linguistics setting itself an object superior to the sentence, since beyond the sentence are only more sentences--having described the flower, the botanist is not to get involved in describing the bouquet.

From the point of view of linguistics, there is nothing in discourse that is not to be found in the sentence: "The sentence," writes Martinet, "is the smallest segment that is perfectly and wholly representative of discourse." Hence there can be no question of linguistics setting itself an object superior to the sentence, since beyond the sentence are only more sentences--having described the flower, the botanist is not to get involved in describing the bouquet.And yet it is evident that discourse itself (as a set of sentences) is organized and that, through its organization, it can be seen as the message of another language, one operating at a higher level than the language of the linguists. Discourse has its units, its rules, its "grammar:" beyond the sentence, and though consisting solely of sentences, it must naturally form the object of a second linguistics. For a long time indeed, such a linguistics of discourse bore a glorious name, that of Rhetoric. As a result of a complex historical movement, however, in which Rhetoric went over to belles-lettres and the latter was divorced from the study of language, it has recently become necessary to take up the problem afresh.

-"Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives," in Image-Music-Text, 82-3

This--an essay one can't reread enough--I think says more perspicuously and less equivocally what Paul de Man tried to get at, though perhaps de Man had his own way of recognizing other functions of this second linguistics which escape Barthes. Nevertheleless, is this not what de Man perhaps should have said when talking about rhetoric (and rhetorical tropes)? Wouldn't that (and the analytical tools necessary to put it in this way) have been more helpful? It's a crazy question, I know, but in studying these rhetorical structures, and in fact calling for a resurgence in rhetorical attention as well as instruction (which de Man did), putting it the right way is the most crucial thing. For instance, de Man would never make that nod to "transitions" between the sentence and what lies beyond it that for Barthes here "goes without saying:" de Man would emphasize how this "beyond" is a nearly absolute gap. And that seems to me to imply a whole different way of going about analyzing rhetoric--one which is much more likely to be irresponsible. (Derrida, for his part, would show that the beyond is absolute only as a form of being nearly-absolute, as a form of absoluteness which we are always unsure is absolute, which brings him actually closer to Barthes than de Man, I think: the failure of the gap to be absolute precisely means that we have a responsibility to find, locate, theorize, play with the "transitions.")

Sunday, February 8, 2009

"L'accent compte:" Displacing the text, continued

I forgot to mention the crucial experience that really, for me, forms the essence of close reading and underlies my willingness to characterize it as a displacement of the text, as I remarked a few days ago. Or, perhaps to put it in a better way, there is a singular function that close reading can set to work which is of the utmost value and brings about what I call the displacement or the delay in communication that actually constitutes the text.

I forgot to mention the crucial experience that really, for me, forms the essence of close reading and underlies my willingness to characterize it as a displacement of the text, as I remarked a few days ago. Or, perhaps to put it in a better way, there is a singular function that close reading can set to work which is of the utmost value and brings about what I call the displacement or the delay in communication that actually constitutes the text.This function is one of allowing an ever so slight, but extremely crucial shift in the tone of a sentence (say), such that this sentence can be read in more than one way. The easiest and most simple example I can give is sarcasm:

That's a really nice job you did there.

There are basically two widely different meanings here depending on whether I read the sentence as sarcastic or not. And it isn't so much that these meanings inhere in the sentence itself (in the language and in linguistic convention), although its phrasing contains their possibilities. It is really that reading actuates these possibilities and actually constitutes the sentence depending on how it proceeds: if I read it as sarcastic, the word "job" loses some of its ability to signify an actual job, and becomes more idiomatic, less referential, and (appropriately) wider in scope (it can weirdly refer to more things, in losing its referentiality). The word "there" changes in a similar way. You can see then--despite this being a poor example--the work of tone. I.A. Richards defines tone usefully as the way that one communicates a sentence to another: it is for him "the speaker's [or writer's] attitude towards his audience," as he says in Practical Criticism. Notice that this is very far from something line intention: it is closer to the sort of general directedness of the sentence itself, such that one would rather speak of the intention of the sentence.

The point though, is that the function of close reading is to show that there is never merely one intention to our sentence. Or, since the work of reading actually brings out more of these intentions as it proceeds to consider or discuss the sentence, we can say that the function of close reading is actually to make possible the multiple tones with which something might be understood. It both shows that there are multiple intentions, multiple ways something can be said, but it also makes possible, by accessing tone or the possibilities of tone (which perhaps would not then be reducible to the tonal possibilities inherent in the language itself) the existence of these different ways beside each other, ranged out as it were before us. The work of close reading would then be to fold them back into the sentence as more and more of these ways are proffered in discussion. This would be the work of delay and displacement which actually--in resisting totalizing the text--actually constitutes it, which I talked about before.

This all sounds complex, but it's actually what is going on in any good close reading of a text--or at least this is my claim. It is a function that has produced many great readings over the years.